WESTERN HIGH SCHOOL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, ’14

Author: The Yearling, Cross Creek, other works

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was one of the best known writers in America. Three of her books were best sellers, and one of them, The Yearling, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and was made into a movie nominated for six Academy Awards. Today, many people have to be reminded who she was.

But Rawlings herself probably would not have minded. Few writers have had a deeper sense that life does not end with fame or mortality, that we are part of a much greater scheme. After witnessing the birth of a sow one day, Rawlings wrote, “This was the thing that was important, to know that life is vital, and one’s own minute living a torn fragment of the larger cloth”.

Rawlings was not the first member of her family to appreciate the tenuousness of human existence. She came from a long line of pioneers. One of her father’s ancestors was the first Dutch minister to arrive on Manhattan Island in the early 1600s. On the maternal side of her family were farmers who helped settle the state of Michigan.

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings was born in Washington, DC, on August 8, 1896, to Arthur and Ida Kinnan. By the age of 6, Marjorie was already writing poems, but her literary debut came at 11, when The Washington Post printed one of them on its children’s page. National recognition came five years later when McCall’s magazine published her first story. At 18, Marjorie enrolled at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where the majored in English and wrote for almost every publication on campus. By the time she graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1918, she had fallen in love with Charles Rawlings, a fellow student. Not long after they married, however, the romance faded. Her dreams of writing dimmed by “humdrum domesticity”. Marjorie tried to escape the malaise by turning out feature for the Louisville Courier-Journal. But to her it was “a scrappy kind of writing”, far from the fiction she so desperately wanted to create.

Hope, as usual, came from an unexpected quarter. During a visit to Florida in 1928, Marjorie saw its orchards and rivers for the first time and suddenly felt that she had “come home”. Six months later she put a down payment on an old farmhouse and 72 acres of orange and pecan trees in Cross Creek, Florida.

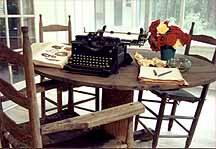

“Boiling over with new ideas”, Marjorie threw herself with relish into a life of farming and writing. By the spring of 1930 both were bearing fruit. Shortly after her first harvest, Scribner’s magazine bought her sketches of the Crackers, trappers and farmers who lived in Florida’s backwoods. After years of trying to write slick stories about fashionable sophisticates, Rawlings had finally found her true subject: the power and beauty of a land riddled with snakes and rivers. The second piece Rawlings submitted proved even more important, for it attracted the attention of Maxwell Perkins, the editor who had discovered F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, and Ernest Hemingway, and who had a special gift for turning good writing into great art.

With a push from Perkins, Rawlings began her first novel, South Moon Under, in 1931. While revising the manuscript she fell prey to double malaria, as well as marital problems. Charles, a sailor and sportswriter, preferred New York regattas to farm chores, so he was away much of the time. This left Marjorie, with little experience and even less money, to feed the chickens, milk the cows and tend 4,000 trees on her own. She was down to her last box of biscuits and a can of soup when one of her short stories garnered a $500 prize. The windfall restored her bank account, but not her marriage. Shortly after South Moon Under was published to rave reviews in 1933, she and Charles decided to get a divorce.

Before their breakup, Charles had suggested to Marjorie that she write a children’s book. In 1935, on one of her excursions into the Florida wilderness, Rawlings found the setting and inspiration for what would become The Yearling. She had met an old pioneer who recalled that, as a boy, he had had to shoot his pet deer. Although the incident had occurred 50 years earlier, “It hurted me all my life.” Marjorie’s imagination took flight. With typical gusto, she began writing 8 to 12 hours a day, “going perfectly delirious with delight”. When The Yearling was published in 1938, critics compared it to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and predicted it would become an American classic.

A self-described hermit, Rawlings was fond of saying “If I had to choose between trees and people, I think I should choose trees.” The one exception was Norton Baskin, a handsome hotel owner whom Marjorie married in 1941. The other great love in Rawlings’s life was her home in north Florida, to which she gave full expression in the book Cross Creek. Although it is often called an autobiography, Cross Creek makes almost no mention of personal events. Its real subject is the spirit of Rawlings’s rural community – the men and women, rattlesnakes and mules – that helped her see the wonders of the Creek.

Its publication in 1942 won Rawlings a new place in American literature. Delighting in the antics of the Crackers, some critics praised her distinctly American humor; others, moved by her powerful descriptions of nature, hailed her as “a female Thoreau”. The response that meant the most to Rawlings, though, came from World War II servicemen, such as the sailor who ran back to his locker to get Cross Creek before abandoning his sinking ship. Although Rawlings’s feelings for Cross Creek ran deep for the rest of her life, she was never completely at peace there after the runaway success of The Yearling. With fame came tourists, whose brash intrusions forced Rawlings to find quieter places to write. Perhaps worse, when Cross Creek was published, a neighbor named Zelda Carson took umbrage at Rawlings’s depiction of her as “an angry and efficient canary” and – proving the point – sued the author. The case was initially decided in Rawlings’s favor but on appeal, Carson won a dollar in damages. Rawlings, who put great stock in her friendships, was devastated by Carson’s accusations. But one by one other neighbors assured her that the book had done no harm.

Not even the kindness of neighbors, however, could assuage the increasing inner turmoil Rawlings suffered as she grew older. Though she continued to enjoy great success – magazines kept publishing her stories and Hollywood began asking her for scripts – both her physical and emotional health began to crumble. Restless and depressed, Rawlings turned with greater frequency to alcohol and soon found it impossible to quit.

Hoping a change of scenery might bring solace, in 1947 she bought a home in the New York farm country that had been settled by her ancestors. But on the eve of, her move, she was dealt another blow: news of Maxwell Perkins’s death. The loss was both personal and professional, and her first impulse was to abandon her work. “Writing without Perkins’s guidance was more of an anguish than ever”, she admitted. “I shrink back in horror from every phrase.” And yet, once again drawing on the philosophy of Penny Baxter, the wise father in The Yearling, Rawlings “took it for her share” and went on. In 1953 she published The Sojourner after struggling with it for 10 years. The novel promptly took its place on the best-seller list beside Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.

It was Rawlings’s last book. Although she managed to keep up her usual round of visits to friends in New York and embarked on research for a biography of the Virginia novelist Ellen Glasgow, her health was giving out. Alone without a telephone at Cross Creek, she suffered a heart attack one evening. Help didn’t come until the next morning, but Marjorle said she had not been afraid. “Death seemed cold and dark and lonely, but I seemed to be looking down a straight road overarched by trees, and the road simply went on with no end in sight.” Six months later, on December 15, 1953, Rawlings reached the end of that road. While playing bridge with Norton and two of their friends, she was stricken by a cerebral hemorrhage and died the next day.

Rawlings was buried, as she had requested, near the Florida grove she loved so dearly. At her grave, her friends read these words from Cross Creek:

“It seemed to me that the earth may he borrowed but not bought. It may be used but not owned. It gives itself in response to love and tending…. But we are tenants and not possessors, lovers and not masters. Cross Creek belongs to the wind and the rain, to the sun and the seasons, to the cosmic secrecy of seed, and beyond all, to time.”

Today, Cross Creek is an historic landmark, which, like Rawlings’s work, can be enjoyed for the moment but ultimately belongs to a larger world.

Source: Biographical material taken from an account in a leaflet published by Reader’s Digest, Inc. in 1993 and reprinted in The Echo, 2001.